Part 4.2 of the Critical Thinking Series (CTS): The Fallacies

Middle-ground and other-ground fallacy, aka middle-ground fallacy; argument to moderation; false compromise.

Definition and General Overview

When people or groups disagree about two competing ideas, someone else assumes a conclusion that does not overwhelmingly favor one side must be better (e.g., more accurate, tasteful, ethical, viable, etc.) simply because it is in the middle (or roughly in the middle) of two competing ideas, or a different conclusion altogether.

Compromise is an integral part of our personal lives. My wife and I certainly make plenty of compromises in my family.

Compromise is especially critical in the free society of a democratic republic, where public discourse helps us arrive at collective decisions. Indeed, being flexible enough to compromise on many issues is a sign of being reasonable. However, it is fallacious to default to such a position without honestly assessing the merits of the competing arguments and how that different idea compares to the others. That is an unreasonable mode of thinking. Granted, that person may be accidentally correct. A broken sundial is right twice in a blue moon…or something. That different idea may be better, but for reasons that person failed to adequately consider. We should assess the merits of arguments (including our own) to help us arrive at well-supported conclusions.

This fallacy is pretty much the opposite of the excluded middle fallacy and is highly related to the false balance effect. However, this fallacy should not be confused with fair negotiation and compromise.

This fallacy takes the general format:

Given: A and B are competing ideas.

Assumption: Competing ideas are almost always too flawed.

Conclusion: Thus, some other option must be better.

Specific Forms

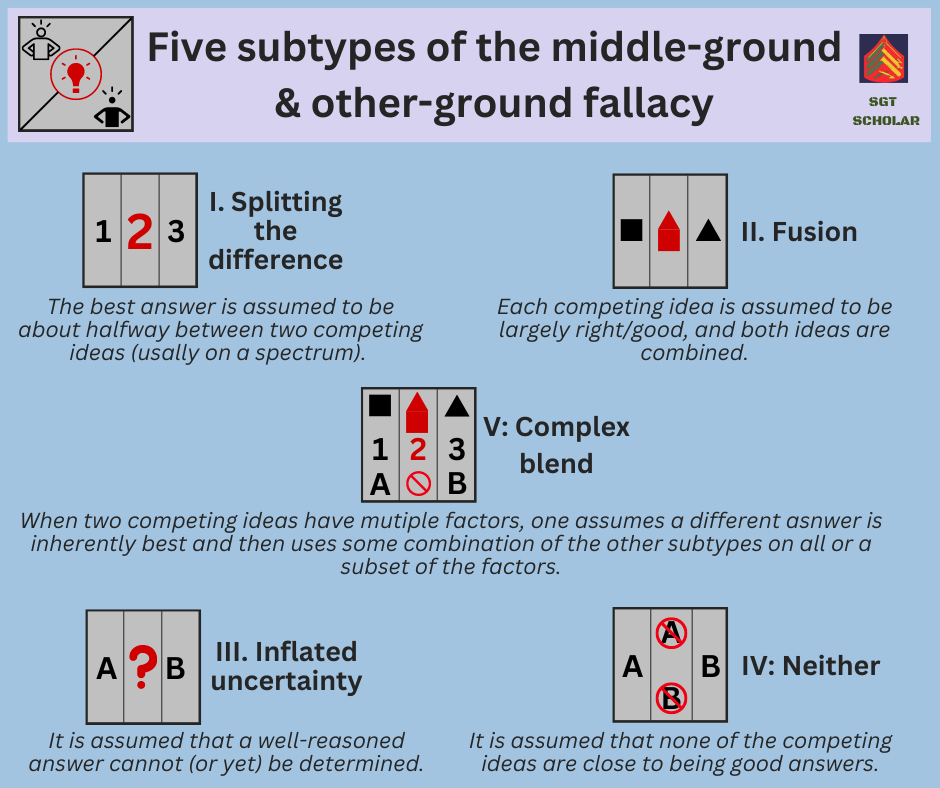

When I began writing this, I came across a blog by Bruce Thompson of Aplomar College. Thompson identified two general middle-ground forms. I like Thompson’s main ideas, and it got me thinking. So, I shifted my last three operating neurons into overdrive and pondered this fallacy more deeply. My thought train sometimes crashed and burned, but that was probably the alcohol. Anyway, after cogitating the crap out of this, a few insights crystalized. First, I think it is more clear to include the phrase “other-ground” with “middle ground” to highlight that not all types of “middle” are the same (as we will soon see). Second, in my current view (which is worth precisely what you pay for), there seem to be four general types, with a fifth representing a complicated mixture, as shown below.

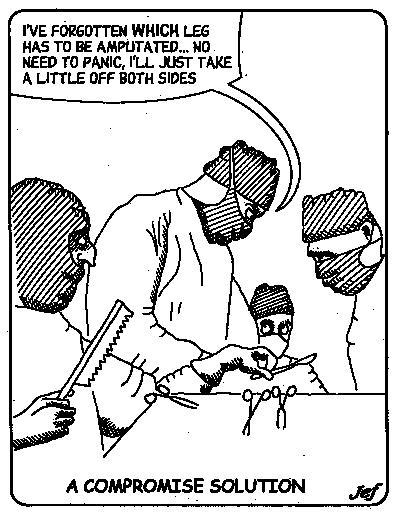

Splitting the difference

Without considering the two competing ideas, one assumes the best answer is roughly in the middle—without overwhelmingly agreeing with either side. One assumes splitting the difference between the opposing ideas (usually on a spectrum) is the best option merely because it is in the middle. It takes the following form:

Given: Claims A and B disagree with each other.

Assumption 1: competing claims almost always are extremely (and about equally) far from being accurate, ethical/tasteful, viable, etc.

and/or

Assumption 2: Independent thought is essential, which means agreeing with either side is a sign of lacking independent thought.

Conclusion: a better (or more socially desirable) answer is about halfway between A and B.

This form occurs more readily on ideas that exist on a spectrum, ordered series, or hierarchy of some kind. However, (*adjusts monocle*) sometimes ideas can be force-fitted on such a spectrum. King Solomon threatening to slice a child in half comes to mind. Not to split hairs (so to speak), but I think half of a former animate body is a somewhat different concept than a living child. Granted, that’s not why he allegedly threatened this, but I think you pieced together what I’m trying to say: it is possible that people will try to use “split the difference” when the nature of the concept cannot be clearly split.

Fusion

Here, one assumes the best answer is to largely agree with each competing idea. Instead of “splitting the difference,” they are largely combined. Again, this is done without actually considering the merits of each argument. Fusion takes the following form:

Given: Claims A and B disagree with each other.

Assumption 1: competing claims almost always both share a large (and approximately equal) level of truth, ethics/taste, viability, etc.

and/or

Assumption 2: objectivity is essential, which means disagreeing more heavily with one side is a reliable sign of unfair bias.

Conclusion: a better (or more socially acceptable) answer must agree with both, sharing large parts of both A and B.

This form is easiest to use with claims that can’t be easily placed on a series, spectrum, or hierarchy of some sort.

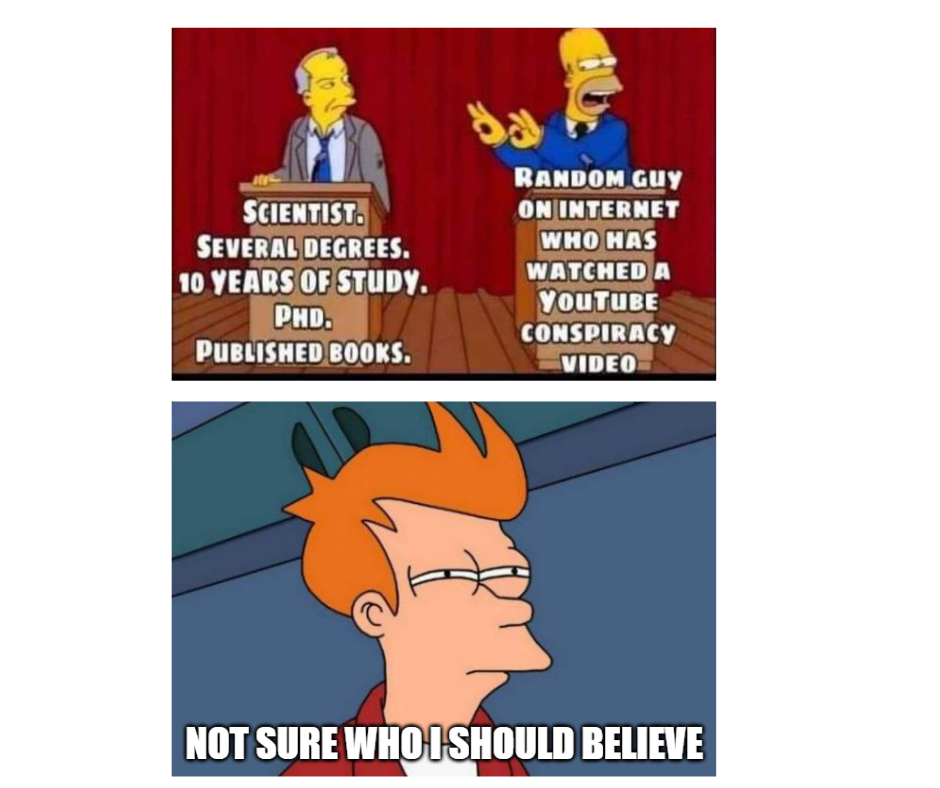

Inflated uncertainty

Here, one has an overly inflated sense of uncertainty when enough information is present to make a reasonable decision. One then erroneously assumes that a reasonable decision cannot be determined, or at least cannot yet be determined. Thus, one neither accepts nor rejects any position and says, “Gee golly wilikers, I just don’t know what to think here.”

Inflated uncertainty takes the following form:

Given: Claims A and B disagree with each other.

Assumption 1: disagreements indicate that no reasonable answer can currently be achieved

and/or

Assumption 2: disagreement is uncomfortable.

Conclusion: a better (or more socially desirable) answer is to take an “I don’t know” approach.

Inflated uncertainty often results when powerful people and organizations use their influence to artificially sow doubt among the public with messages that distort the truth. These manipulative asshats make it seem like the evidence is inconclusive when the evidence actually robustly supports a clear conclusion. This tactic is often called inflation of conflict and includes examples such as tobacco companies manipulating the public’s confidence in science to downplay cancer risks, petroleum companies using the same playbook about the threats of leaded gasoline, and, yes, fossil fuel industries using the same playbook about climate change. See that link for more.

The inflated uncertainty subtype is somewhat similar to at least two other fallacies: appeal to ignorance and appeal to incredulity. However, these fallacies are different in key ways. In appeal to ignorance, uncertainty is used to assert something is true (rather than unknowable), and in appeal to incredulity, a personal difficulty in understanding something is used to assert something (often complicated) is false. Inflated uncertainty differs from those two fallacies by overemphasizing a small degree of uncertainty not to justify a perceived true (or mostly true) conclusion but an answer that translates to “meh, who knows.”

However, not all instances of inflated uncertainty are necessarily fallacious. For example, if two friends are aggressively bickering over something silly, then maybe not taking a side is the better choice. Here, the goal isn’t “let’s determine who is right” but rather “let’s get back to having some respectful, friendly fun, you cantankerous fecal sticks.”

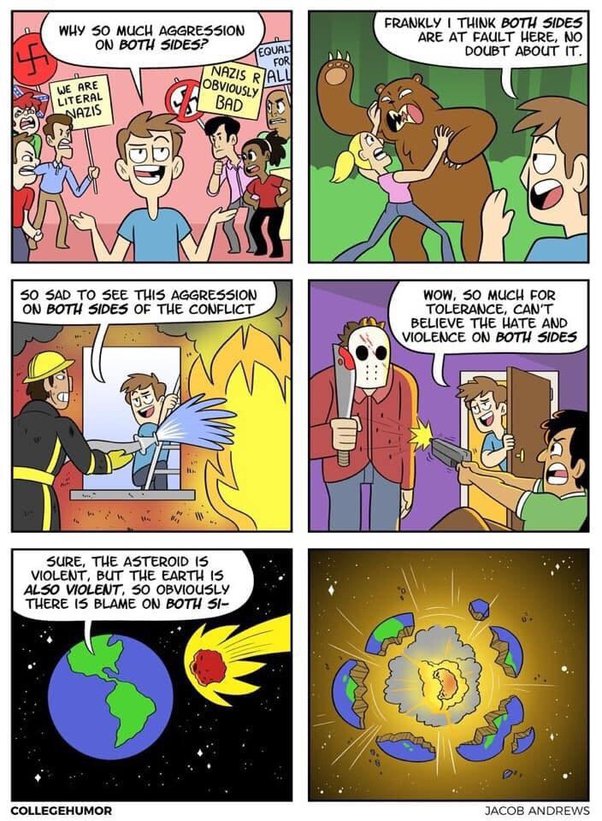

Neither (or none of the above)

Here one largely rejects competing ideas (without actually considering them) in order to advance a “both are wrong” position. One assumes that both sides are entirely or largely wrong and perhaps some other option (or no option) is best. This subtype takes the following form:

Given: Claims A and B disagree with each other.

Assumption 1: competing claims almost always are extremely (and about equally) far from being accurate, ethical/tasteful, viable, etc.

and/or

Assumption 2: Independent thought is essential. Disagreeing with both sides shows independent thought.

Conclusion: disagreeing with both is a better (or more socially desirable) answer.

Complex blend

This is merely a blend of subtypes when trying to find a middle-ground or other-ground option between two complex ideas.

Caveats

One should not come to the impression that middle-ground or other-ground answers are always wrong. No. An answer is not better or worse just because it is different or some version of in-between. It’s all about evidence and reasoning. After all, it was long argued that light was either a particle or a wave before enough evidence accumulated to show light is an entity with both properties. So yes, middle-ground answers can be true, but again, it’s all about evidence and reasoning. I made that last sentence in bold and italics to help drive the point home, but I feel like it needs emphasized more….

Recall that there are three overarching types of claims an argument can make: one of fact, value, and/or policy. Though the middle-ground fallacy can be applied in questions of value and policy, in my view, this fallacy most clearly applies to arguments about questions of fact. After all, the sky is not green just because someone argues it is blue and another argues it is yellow. Questions of value and policy involve more subjectivity, which is not always as clear, but that is fine. We need to determine and accept some set of values, and we must make all kinds of decisions. But we should not choose middle-ground or other-ground options for the sake of choosing middle/other-ground options.

On that note, this fallacy is different from compromise. By compromise, I mean finding a course of action or decision that is reasonable enough for the people/groups involved. A set of reasons must exist for all parties to find the terms acceptable. However, if one party is forced or coerced to agree to a set of terms, then that is manipulation, not compromise.

Light-hearted examples

Before diving into some serious subjects, let’s look at some examples that are less serious to help show how these forms of the fallacy work.

Example 1 (Fusion)

Doug Graves: Zombies are real, brother.

Phil Graves: No, brother, there is no evidence to support that.

M. Balmer: Zombies are not real yet, but they will be.

M. Balmer combined both claims and gave no evidence to show this middle-ground conclusion will be true, thus satisfying the dark hopes of zombie-preppers itching to use a fully automatic 50-caliber machine gun on waves of the undead assaulting their cabin. To be fair, that does sound badass. Utterly terrifying, but badass.

Example 2 (Inflated uncertainty)

Doug Graves: Zombies are real, brother.

Phil Graves: No, brother, there is no evidence to support that.

M. T. Graves: Who knows, brothers… Who knows.

Here, M. T. Graves inflates the uncertainty to advance an “I don’t know” position when in reality, combining 1) lack of evidence of zombies and 2) no known mechanism for zombies to be a reality is a good indicator to safely assume zombies are fiction—at least until robust evidence comes to light (if ever). And if they ever do come, they will have to sacrifice many undead bodies to eat my brain’s last three neurons.

Example 3 (Splitting the Difference)

Matt M. Maddox: 7 + 8 x 3 = 31 because of PEMDAS.

Loise D. Nominator: no, it’s 45 because we go from left to right.

Ron Umber: Uhm, I think it is 38…

Ron merely chose a number that is halfway between 31 and 45. He literally split the difference. Per the rules of PEMDAS, the correct answer is 31.

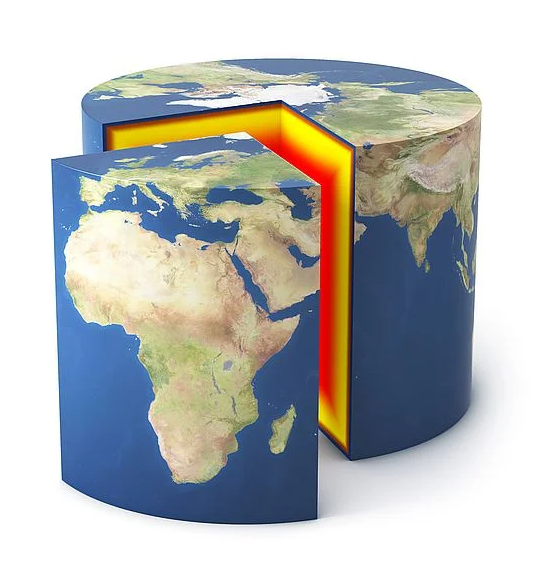

Example 4 (Fusion)

Stu Pitt: The Earth is a flat disc.

A fifth grader: No, the Earth is spherical. Granted, it’s not perfectly spherical—it’s more like an oblate spheroid—but it is not flat.

Mo Ron: Maybe the Earth is a cylinder.

I shouldn’t have to explain this one. But if you want, one of my earlier blogs was a series that explains how we know the Earth is roughly spherical, and the commonalities between the arguments of flat Earthers and other pseudoscience advocates here.

Example 5 (Neither)

B. Anna Peele: Eating bananas is morally wrong. It’s phallic-shaped. People need to stop doing it.

Carmen Sents: What?… Yeah, morals are pretty subjective, but c’mon. Eating a banana is morally wrong? It’s a fruit. I can understand arguments about how eating animals is wrong. But fruit is not sentient. It cannot feel pain. Many plants literally evolved for animals to eat fruit and disperse seeds. Plus, what on Earth does the shape of food have to do with ethics? Look, if you wish to not eat bananas, be my guest, but don’t expect any of us to take this view of morality seriously. Isn’t that right, Ike?

Ike Kahn O’Clast: You’re both wrong. It’s immoral to debate ethics.

Carmen Sents: You’re killing me, Ike…

Ike disagreed with both Carmen Sents and B. Anna Peele, opting for a “middle” position that they were both wrong. On top of that, Ike literally argued about ethics, which I guess would be immoral to him? Anyway, you get the idea.

Examples in more important topics

Now let’s dial in on some more serious topics. But, of course, this is Sgt Scholar, so yes, the name puns will continue.

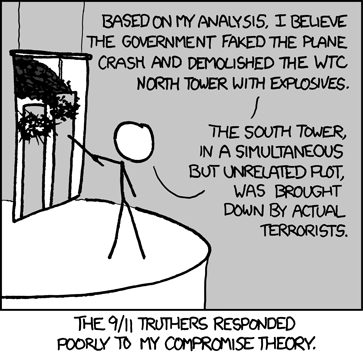

Example 6 (Complex blend)

Clay Matt: Climate change is definitely real and human-caused. If you want to know how we know this, Sgt Scholar cites and describes the key evidence. He may be a crayon-eating Jarhead, but he uses credible sources and breaks down the science.

D. Nyer: Nuh uh. Humans can’t change the climate. Climate change is a worldwide hoax.

Luke Warm: How about we agree that climate change might be true, but not human-caused.

Though the climate changed slowly in the past, the evidence overwhelmingly shows it is currently changing relatively rapidly because of human activities. But if it was natural, it would not be just because that potential answer is different from these two competing claims. FYI, I have several resources about climate science if you want to learn more.

Here a blend of at least two subtypes of this fallacy were used. The argumetn between Matt and D. Nyer revolves around two questions: if climate change is real or fake, and if climate change is primarily human-caused or natural. Concerning the first question, if it is real or not, Luke used inflated uncertainty to claim “it might be true.” There is more than enough evidence to determine this. Luke then used “a neither option” to advance the idea climate change is natural. Because D. Nyer views it as a hoax, by default, he doesn’t believe it is natural because it is not even true to begin with. And Matt didn’t advance this option either. Thus, claiming it is natural takes a “you’re both wrong” stance.

Example 7 (Splitting the Difference)

Clay Matt: Climate change will not likely lead to a literal apocalypse, but without responsible and viable large-scale solutions, the negative consequences will progressively worsen, substantially affecting our health, environment, security, and long-term economic prosperity. It might be too late to avoid all effects, but we can avoid the worst outcomes. The sooner and more we invest in viable solutions (like green energy sources), the better off we will be.

D. Nyer: Climate change is real, but these alarmist predictions are purely false. They just want to raise taxes and make money through fear. We do not need to act because the impacts will be negligible. I mean, CO2 is plant food for krikey’s sake.

Luke Warm: If we do nothing, I think the consequences will only be moderately bad.

Here, the people involved are arguing about consequences that fall on a spectrum (very bad, bad, moderately bad, none, etc.). One side argued it can be substantially bad (depending on how much we prevent), with the consequences worsening over time. In contrast, the other side argued the negative consequences would be negligible. Luke split the difference between these views, saying it will be only moderately bad.

FYI, I have several resources about climate science if you want to learn more.

Example 8 (Inflated uncertainty)

M. Ed Hassan: homeopathy is bovine scat. Science shows it does not work.

Estelle Hurtz: homeopathy is a real medicine with amazing powers.

Macon Payne: the science is still undecided.

No. Homeopathy contradicts known science. Water does not retain the properties of substances it was in contact with. If it did, I would never buy another beer. I would keep diluting the same one. Also, diluting something does not make it more powerful. This contradicts the known laws of physics and chemistry. It would take extraordinary evidence to show our understanding of fundamental principles of physics and chemistry are seriously flawed. Unless such evidence comes to light, we can safely reject homeopathy. See here for more.

Example 9 (None of the above)

Ms. N. Fermischin: Growing these unnatural Frankenfood GMOs is bad because they make us unhealthy. We need to go all organic to feed our growing world nutritious food.

Eaton Wright: I disagree. First, as an outdoorsy person, I find nature lovely and fascinating. Being “natural” seems appealing in part because we value protecting nature. But whether something is natural or unnatural tells us nothing about being bad or good. After all, a field full of crops is not exactly natural. Taking pain medicine, treating cancer, wearing corrective glasses, calling our loved ones on the telephone—none of these are natural, per se. Second, human health is critically important, which is why GMO safety has been extensively researched. The good news is thousands of studies show no negative impact on human health. Third, this biotechnology increases crop yields (including previously hotly debated corn yields) while reducing pesticides, and often requires less water and land. Fourth, these benefits keep costs down for both the farmers and consumers—which can help increase access to affordable, nutritious food for more people. The point is we can feed more people for fewer costs and with less environmental impact without sacrificing health, which is pretty good IMHO.

Miss Anthrope: You’re both wrong. GMO’s allow us to grow more food, which means more people, and people are bad. Instead of discussing ways to feed the world, we should be talking about ways to eliminate humanity. Humane methods are preferred, but I’m open to suggestions.

Granted, I don’t think many people would agree with Miss Anthrope’s position. So why did I use this example? Two reasons. First, if I’m being honest, I wanted to use this opportunity to help dispel myth-information about GMOs. Second, I wanted to show how the forms may seem to overlap. One may be tempted to say fusion because it acknowledges GMOs benefits and combines it with a general conclusion of GMOs being “bad.” But I think none-of-the-above is a much better fit. Remember, the fusion form views both competing ideas as largely correct, whereas none-of-the-above views both competing ideas as largely wrong. Miss Anthrope’s conclusion drastically deviates from feeding a growing population nutritious food—a goal shared by Ms. N. Fermischin and Eaton Wright. It seems, at least to me, that Miss Anthrope disagrees with each argument more than she agrees.

Non-examples

Non-example 1

Stu D. Baker: My asking price for this car is $30,000

Lisa Carr: I’ll pay $25,000

Stu D. Baker: I’ll accept $27,000

This is merely negotiation (and it seems like this is a reasonable offer).

Non-example 2

Crystal Claire Waters: I think this adult Humpback whale weighs 40,000 pounds.

Misty Shore: I dunno, it seems large. Maybe it is 90,000 pounds.

Jack Kehstow: Well, we don’t have any measurements, but according to the National Wildlife Federation, a Humpback whale typically weighs between 50,000 and 80,000 pounds. So there is a good chance this whale is somewhere between those guesses.

Jack noted the true weight was probably in between the two competing claims, but the reasoning is based on data, not guessing something in the middle for the sake of guessing in the middle. After all, if Crystal and Misty estimated the whale was between 10,000 and 15,000 pounds, the NWF’s data would not change to 10 and 15 thousand pounds.

Iterative use:

Interestingly, this fallacy can be applied iteratively in various steps, and in some cases, this conclusion can be close to one of the original options. Consider the following absurd scenario.

Long ago, in the days of the early scrolls, a person (whose name time forgot) passionately proclaimed 20 is the right answer to everything. However, his nemesis vociferously disagreed, claiming 100 is the only true answer to all. They argued for all that day, through the night, and into the dawn. Then a mutual friend (who fancied themselves a sage) offered that 54 was the answer they all sought. If it was good enough for a theater/dance club, then it was good enough for everything else. But the 20-orthodoxist thought 54 was tantamount to heresy and vehemently disagreed. Followers began taking sides. Some adhered to 20. Others to 100, and yet others still to 54. The quarrel continued for a few years, with the adherents of 100 slowly converting to 54. Then some other ultracrepidarian (whom the scrolls only remember by their pseudonym, Mezzo) proclaimed the answer to all was none other than 36. Tired of fighting, the 20-orthodoxists said, “screw it, it’s 36.” However, the 54-supporters were utterly unconvinced by this blasphemy and told the 36-reformationist to eat a “Richard.” (The scrolls are hazy on that translation). The 36-reformationist refused to yield and gathered a following of his own. For centuries, the reformationist 36s and the devout 54s waged war. They launched massive crusades into each other’s heretic-infested land, wreaking havoc and divine terror. Then one day, the emperors of the 36s and 54s decided to settle the matter in one final, epic battle. They amassed enormous armies and met at dawn on an open field. Walls of snarling, stalwart troops stared each other down, ready to embrace victory or death. But as the first light broke, a woman on a Shetland pony slowly emerged from the mist. Bathed in golden rays behind her, she silently rode between the armies. All eyes watched this mysterious, stoic figure fearlessly stroll betwixt the mightiest militaries of all known history. She dismounted and let the air hang still for a few lingering moments. She then drew back her hood, raised her staff, and bellowed, “Rejoice! For the penultimate solution to all ye seek, the meaning to all life, the reason for all existence, the answer to everything doth be 42!” And they wept, for there was now peace at last. Not because they agreed with her. But because they both agreed this was a cheap rip-off of Douglas Adams and meh, that was good enough as any reason to quit fighting.

Here, 42 is much closer to the original 20-claim than th the original 100-claim. But through iterative use, 42 came to be the accepted answer.

See Also

Be sure to like, comment, share, and follow! Click on the topic buttons on the top navigation menu to enjoy more articles.

Click here to support Sgt Scholar on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/sgtscholar.

3 Comments

Comments are closed.