Brief overview

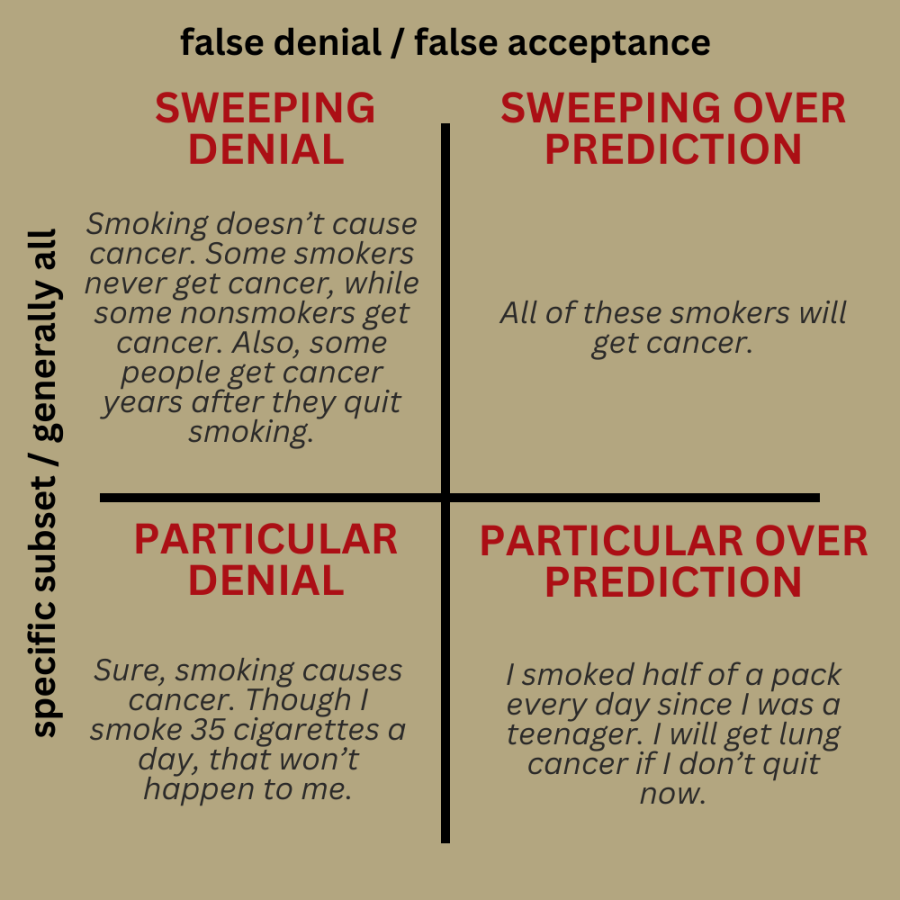

This error in reasoning oversimplifies cause-effect relationships by ignoring how complexity can create degrees of unpredictability. In other words, someone replaces probability with unwarranted certainty. As far as I can tell, there are four overarching ways this is done. I am unaware of any official names, but I describe them in the examples below. Read on for more. Or don’t. I’m a STEM/critical thinking blogger, not your dad… probably.

Forms and examples

For this fallacy, I wanted to use a consistent topic for all the examples, and smoking and cancer risks seemed like a good choice. (Some research is provided in the supplemental information section toward the end). I lost my mom to cancer a few months ago (in February 2024), so allow me a quick moment to say with all of my heart, “Fuck cancer.”

The four general ways this fallacy can be used is to overly apply certainty (in general or in a subset of instances) or to erroneously reject the cause-effect (in general or in a subset of instances).

Sweeping Denial

Here, someone erroneously denies X causes Y in (practically) all situations by ignoring the role of probabilities. I am aware of at least three ways to do this.

- Sometimes, Y happens without X; thus, X doesn’t cause Y.

- Sometimes, Y occurs long after X; thus, X doesn’t cause Y.

- Sometimes, Y never happens, even with X; thus, X doesn’t cause Y.

Let’s look at an example that uses all three of these in one overarching argument.

Eva Denc: Smoking is known to increase the risk of cancer. The more one smokes, the higher this risk.

T. Bakkoh: Smoking causes cancer? Sure buddy. There are lots of people who smoke their entire lives and never get cancer. Also, people who never smoked get cancer. Did ya’ ever think of that?! Also, some people who quit smoking get cancer years after they quit. Take your lies and blow smoke up someone else’s bum.

Though rude, much of T. Bakkoh’s information was accurate. Some smokers never get cancer, some nonsmokers get cancer, and some former smokers get cancer years later. However, the information was coupled with an unspoken and erroneous assumption. This error is more obvious when laid open:

If it’s true that smoking causes cancer, then every smoker (and only smokers) should get cancer while they are smokers. This is not what we see. Thus, smoking does not cause cancer.

This argument blatantly ignores the role of probabilities like an angsty teenager ignoring reasonable advice. A complicated set of variables (like lifestyle, genetics, and environment) influences the risk of getting cancer. Some people get lucky, and some people get unlucky, but all things being equal, people who smoke are more likely to get cancer than nonsmokers. By definition, there will be exceptions to a trend, and seeing such exceptions does not negate that trend.

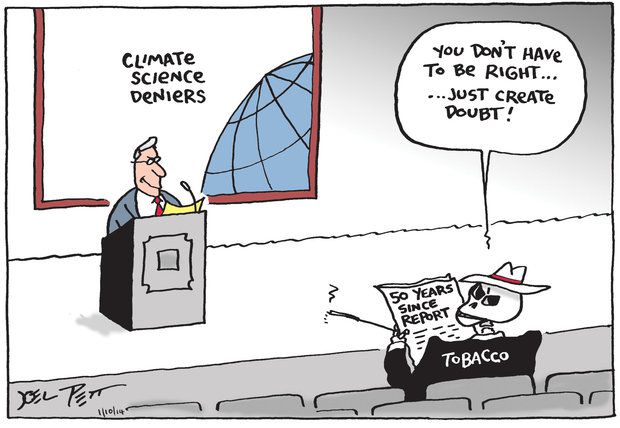

As I’ve said before, fallacies overlap. So, we can view this argument not only as the fallacy of causal determinism but also as a strawman argument because it distorts the opposing argument from “smoking increases the risks of cancer” to “smoking will definitely cause cancer in all smokers, and only smokers.” This twisted argument is easier to attack, because one counter example would disprove it. T. Bakkoh’s argument can also be viewed as a false dichotomy (one of the forms of excluded middle) because T. Bakkoh seems to assume that there is either A) a trend with no exceptions or B) no trend at all. Despite the fallacious reasoning, sweeping denial is successfully used in disinformation campaigns—not necessarily because such tactics make people believe the lies, but because it causes people to doubt sound science (Oreskes & Conway, 2011).

Sweeping overprediction

Here, someone does not deny X causes Y, but they assume Y will (for all intents and purposes) inevitably follow X when the odds don’t support such certainty.

Eva Denc: According to the CDC, as of 2021, it’s estimated that 11% of American adults (more than 28 million) smoke cigarettes.

Z.L. Ott: All of these smokers will get cancer.

Z.L. Ott ignored the importance of nuance and risk. Smoking substantially increases the odds, but a sizable portion of these people will not get cancer. Though this argument is probably not the result of misinformation campaigns, it represents a potential way someone could misunderstand risks.

Particular denial

Here, someone accepts X causes Y, but they downplay the probability of Y in a particular instance or subset of instances.

Eva Denc: smoking increases the risks for many negative health complications, like lung cancer.

Jayne S. Mocain: True, smoking increases the risk of lung cancer, but that doesn’t happen to everyone. Sure, I smoke more than 35 cigarettes a day, but that won’t happen to me.

Jayne accepts that smoking increases the risks. However, he downplays the risks of his actions and (thanks to the powers of denial) concludes he will, in fact, be fine.

Again, fallacies can overlap. This example can also be viewed as an argument from omniscience since the conclusion relies on confidently “knowing” the results of an otherwise uncertain scenario. Generally, more than a quarter of people who continue smoking 35+ cigarettes a day are expected to get lung cancer by age 80, while about 1% of people who never smoked will (Weber, 2021). Of course, this doesn’t mean Jayne, specifically, has a 25% chance of getting lung cancer. That would be a fallacy of division. There are too many variables to confidently translate the risks of the population to a particular individual. Jayne may have a higher or lower risk based on genetics, environment, other lifestyle choices, etc. But despite his delusion, his risk is certainly not zero. Even if we were able to confidently conclude his risk of developing lung cancer by age 100 was only 5%, this is still far from zero. Why did he give such a flawed argument? Cognitive dissonance may have influenced Jayne’s perception. However, this subsection is about the argument, not necessarily the psychological process that influenced their argument.

Particular overprediction

Here, someone knows X causes Y, but they overplay the certainty by ignoring probabilities.

Annita Kwitt: I’m 30 years old and have smoked half a pack every day since I was a teenager. I will almost certainly get lung cancer if I don’t quit now. I am quitting before I become another cancer victim.

Committing to quitting and taking the appropriate steps is a wise choice. The only error with Annita’s reasoning is assuming that she will almost certainly get cancer. Again, as a smoker her risk substantially increases.

Non-example

The chances of surviving a fall from a plane at a high altitude without a parachute are practically zero.

I do not know the precise odds of surviving a fall like this. Still, I imagine they are on par with hitting the lottery jackpot or the wifey and I invited to a private (and very friendly) Twister competition with Jason Mamoa and Scarlett Johansson. But a flight attendant named Vesna Vulović was this lucky, if you want to call it that. After her aircraft exploded at 33-thousand feet in 1972, several unlikely factors came together juuust right to allow her the possibility of surviving. Right now, I imagine your face is like this:

Yeah, that was mine too. Check out the link. Anyway, while technically not impossible, the chances of surviving such a fall are so low it’s fair to call them practically zero. So, no fallacy was present.

Tips for how to respond

Ask: Use a series of genuinely polite Socratic questions to better understand their position and let them reflect on the argument’s flaws.

Example: In my understanding, the more X the higher the odds for Y. May I ask what makes you so certain?…

Counter: Debunk their claims, but when possible, show areas of common agreement without making it personal.

Example: I agree with some of those points, such as… however, the evidence I see supports the more X the higher the odds for Y.

Supplemental Information: Smoking & Cancer

Background of perception

There is a mountain of evidence that shows smoking increases the risk of cancer, especially lung cancer. I will not review that mountain here. You can see Caliri, Tommasi, & Besaratinia (2021) for a brief academic overview, and if you want a brief gobbledygook-free overview, you can see Cancer Research UK. But when evidence began accumulating decades ago, tobacco companies launched a massive disinformation campaign to cast doubt on this science in the public’s eye (see Brandt, 2012). For a while, these companies were successful. In the 1950s, about 42% of Americans accepted that smoking causes lung cancer (Marshall, 2015). In fact, this disinformation playbook is used by other corporate disinformation campaigns today (see Oreskes & Conway, 2011). But in time, the lying asshats eventually lost. The scientific truth prevailed, amassing more and more evidence and public acceptance as time marched on. By the 1990s, more than 90% accepted that smoking causes lung cancer, and by 2015, 97% accepted it, including 91% of smokers (Marshall, 2015).

The risks

There is a lot of research on the risks between smoking and cancer. I can’t cover it all, but to give us some idea, I will use the data from a 2021 study involving more than 229-thousand Australian participants over the age of 45 (Weber, et al., 2021).

Cancer comes in more varieties than there are uses for the f-bomb. Compared to nonsmokers, smokers have a 42 percent higher chance of getting at least one of these forms of cancer. However, smokers were seventeen times as likely to get lung cancer. Of course, the rate one smokes influences cancer risk. Compared to people who never smoked, people who smoked 1–5 cigarettes a day were more than nine times as likely to develop lung cancer, and people who smoked more than 35 cigarettes a day were 38 times as likely to get lung cancer. Quitting smoking was associated with lower risk, but those who managed to quit still had a higher cancer risk than people who never smoked. By age 80, an estimated 1% of people who never smoked will get lung cancer, whereas 7.7% of people who currently smoke 1-5 cigarettes a day will get lung cancer and more than a quarter of smokers who currently smoke 35 cigarettes a day. (Weber, et al, 2021).

Of course, complications with the data make it hard to determine the actual risk any single person has. First, there was variability in the age at which someone started smoking and if their smoking frequency undoubtedly fluctuated throughout their lives. Also, the data relies on self-reported smoking rates, and it is possible many of the estimates are off. Hell, many people may have underreported their smoking habits out of embarrassment. Also, other factors like genetics and environment can increase or lower this risk. Regardless, the main idea is clear: the more you smoke, the greater the risk of developing cancer, especially lung cancer. It’s best to never smoke, but kicking the habit is much better than continuously poisoning your lungs.

Sources

Brandt, AM (2012). Inventing conflicts of interest: a history of tobacco industry tactics. American journal of public health,102(1), 63-71. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300292

Caliri, AW, Tommasi, S, Besaratinia, A. (2021). Relationships among smoking, oxidative stress, inflammation, macromolecular damage, and cancer,

Mutation Research/ Reviews in Mutation Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mrrev.2021.108365.

Marshall, TR (2015). The 1964 Surgeon General’s report and Americans’ beliefs about smoking. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 70(2), 250–278, https://doi.org/10.1093/jhmas/jrt057

Oreskes, N., Conway, E. M. (2011). Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Weber MF, Sarich PEA, Vaneckova P, Wade S, Egger S, Ngo P, Joshy G, Goldsbury DE, Yap S, Feletto E, Vassallo A, Laaksonen MA, Grogan P, O’Connell DL, Banks E, Canfell K. (2021). Cancer incidence and cancer death in relation to tobacco smoking in a population-based Australian cohort study. International Journal of Cancer, 149(5), 1076-1088. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.33685

1 Comment

Comments are closed.